Your donation sets the stage for a new season of Boston's most intimate, entertaining and provocative plays and musicals. Our shows make powerful connections with our audiences-- and they are only possible because of you.

In the Round

In the Round

Scenic Designer Cristina Todesco

Tribes is hardly the first time Cristina Todesco has worked with SpeakEasy; her scenic designs have been seen on our stages multiple times in the past few years, including our productions of Red, Reckless, and last season’s Clybourne Park, with its house that aged fifty years during intermission. We talked with Cristina a bit about her creative process, designing in the round for Tribes, and the eternal wisdom of Tom Waits.

Tribes is hardly the first time Cristina Todesco has worked with SpeakEasy; her scenic designs have been seen on our stages multiple times in the past few years, including our productions of Red, Reckless, and last season’s Clybourne Park, with its house that aged fifty years during intermission. We talked with Cristina a bit about her creative process, designing in the round for Tribes, and the eternal wisdom of Tom Waits.

SPEAKEASY: What was the first show you worked on as a designer?

CRISTINA TODESCO: The first show I ever worked on was in graduate school, on a production of Blood Wedding. My experience up to that point had been as a scenic artist working on museum exhibits, retail store features, trade show booths, movie sets, and pretty limited experiences on theater scenery. I spent some time in the rehearsal room and it was a revelation to watch the actors and director work out the story. I also realized at that time that actors can need very little onstage, and it’s best to not get in their way!

SE: Do you have a “usual” approach to a design when you’re just starting out? A method that helps you begin accessing the script?

CT: What I find to be extremely helpful is to learn as much as I can about the playwright, or the time period that play is set in. This is for me to start getting into the world of the play without needing to think about what the “scenery” needs to be. It’s more dramaturgical for me. With a young, living playwright, this can sometimes be difficult; I love reading as much about the playwright’s background as I can, going to the library and having any aspect of the play accessible to me. However, in approaching Tribes, I knew nothing about the Deaf culture, so I needed to find some good resources to understand the seed of the play. Billy is deaf and he was never allowed a means to enter the Deaf culture. I watched the documentary Sound and Fury, and it gave me a glimpse into what it was that Billy missed out on, and the emotions that get wrapped up when your child is born different than you are.

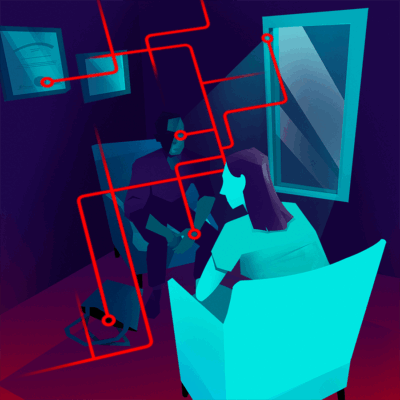

SE: Tribes is being performed in the round, which is a much different set-up than normal for SpeakEasy. What were the biggest challenges and opportunities of this configuration?

CT: I really enjoy tackling a new way of physically experiencing a play, especially in a space that I’ve designed in before. I’ve never seen anything performed in the round in the Roberts, so it was very exciting and inspiring for me to see it in a different way and have the opportunity to change the energy of the space. The particular challenge here was to create several different spaces where people could congregate in this representation of the first floor of their house. We wanted to embrace the literal messiness of this family’s life with all their furniture and stuff, but still allow fluidity and an elegance of movement in the scenes, and of course good visibility from every seat. Bevin and I will work until the last minute to make sure all of the above is happening on stage, and that means changing furniture pieces and changing acting blocking if we have to.

SE: What is your favorite part of the design and production process?

CT: I think the most exciting part for me is the beginning stage, when I’m researching and working out the mechanism of the script, and how to make the play and the action move on paper. I also really enjoy seeing run-throughs of the play in the rehearsal hall. It is very informative for the final stages in the process before opening- to see what has developed in the actors’ performances and the staging and what else I can do to feed this part of the process and take it further, finding more nuance, complexity and depth. It may occur to me that there’s a better chair for that actor’s dialogue to be delivered from, or maybe less clutter would help this scene, or maybe all the doors should be open when this scene happens. I can get a lot of information from watching the rehearsals.

SE: What, to you, most makes for an effective scenic design?

CT: A lot of people say scenery should never comment on the play. It sounds like such an aloof statement but when you imagine that the play can be a metaphor in itself, we need to allow the audience the space to imagine themselves there and make their own personal connections to the piece. If anything, those creating the event need to allow that experience to happen. They need to allow the play to breathe and really be heard, not to illustrate or verify. I remember listening to Tom Waits say something really interesting about writing soundtracks in an interview, which struck me as so right: “If two people know the same things, one of you is unnecessary. And I think a song is kind of a movie for the ears. So if it’s just underscoring and restating what you’re already experiencing visually, I think you just kind of bat it away like a fly unless it has some kind of nourishment from another dimension.” The magical part on stage is that all the elements, both auditory and visual, must be perceived as one voice working for the same intention. That’s the big challenge.

SE: What’s one of the most memorable designs you’ve worked on? Any favorites from other designers?

CT: That’s a hard one because I seldom really remember a design alone. If I was able to really lose myself in the performance, then the design was good. I really like when an economical design facilitates the action and they become one- like in Les 7 Doigts de la Main’s Mad Circus. I really remember enjoying the entire show, but I remember very little of what it all looked like.

Past Productions

Past Productions JOB

JOB The Antiquities

The Antiquities Swept Away

Swept Away