Please consider making a philanthropic gift to SpeakEasy Stage. Your donation will help us build and strengthen our community for the next 30 years.

Dramaturgy

Dramaturgy

Go beyond the stage with our dramaturgy hub, your source for deeper context, artist insights, and creative inspiration behind SpeakEasy’s 2025–26 Season. Explore the themes, histories, and ideas that shape each Boston and New England premiere, and discover how our artists bring these powerful new stories to life.

THE ANTIQUITIES

Written by Reyn Ricafort (Artistic and Engagement Fellow)

Artificial Intelligence

Artificial Intelligence, especially Generative Artificial Intelligence, has become an incredibly powerful tool, with far-reaching implications on human thought, societal structure, and cultural advancement. Harrison’s Antiquities speculates a future where some of society’s concerns about AI come true, offering us a glimpse into the qualities many often percieve as sacred to humanness and how technology like artificial intelligence complicates those perceptions, or perhaps, outright squanders them.

What is Artificial Intelligence?

Artificial Intelligence (AI) refers to the field of computer science concerned with systems capable of mimicking human intelligence and performing tasks like learning, reasoning, problem-solving, and language comprehension. Learning from large quantities of data, AI models are able to make decisions, improve from past mistakes, and streamline future decisions. Their ubiquity in contemporary society makes them present in fields like healthcare, manufacturing, education, and customer service.

A Brief History of AI

Birth of AI (1950 – 1956)

1950: Alan Turing publishes “Computer Machinery and Intelligence,” which proposes a test of machine intelligence called the Imitation Game, or the “Turing Test.”

1955: John McCarthy coins the term “artificial intelligence” during a workshop at Dartmouth College.

AI Maturation (1957 – 1979)

1979: The American Association of Artificial Intelligence–now the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence (AAAI)–is founded.

AI Agents (1993 – 2011)

1997: Deep Blue, an AI system developed by IBM, beats world chess champion Gary Kasparov, becoming the first program to beat a human chess champion.

2006: Companies such as Twitter (now X), Facebook, and Netflix start incorporating AI systems into their advertising and user experience (UX) algorithms.

2011: Apple releases Siri, the first popular virtual assistant.

AI Renaissance (2012 – present)

2015: Elon Musk, Stephen Hawking, Steve Wozniak, and over 3,000 others sign an open letter to the world’s governments banning the development (and later use) of autonomous weapons for war purposes.

2020: OpenAI starts testing GPT-3, a model that uses Deep Learning to create code, poetry, and other language and writing tasks. GPT-3 is the first of its kind that creates content almost indistinguishable from that created by humans.

2021: OpenAI develops DALL-E, which can process and understand images enough to produce accurate captions, moving AI one step closer to understanding the visual world.

Generative AI

Although contemporary discourse can make it seem like AI is exclusive to the immediate present, conceptions of AI goes as far back as the mid 1900’s, with discussions of a “thinking” machine predating modern civilization. So, what can explain the sudden fervor about AI these past few years?

Most of the time, when people today talk about AI, they are likely referring to Generative AI, AI models that can generate new content–text, speech, audio, video, images–in response to a user’s prompt. These models are built on complex systems called machine learning, and more specifically, deep learning. A well-known example of Generative AI is OpenAI’s ChatGPT.

Machine learning (ML): A subset of AI that enables computer systems to learn from data, identify patterns, and make predictions without being explicitly programmed. This allows the computer system to imitate the way humans learn, decreasing human involvement.

Deep Learning: A type of machine learning that uses multi-layered artificial neural networks modeled after the intricate structures of the human brain. This allows the computer system to make complex decisions from large amounts of data, learn without supervision, and make its own predictions.

Natural Language Processing (NLP): NLP refers to algorithms that enable computer systems to understand speech and text as humans do.

Many have expressed concerns about the rapid growth of Generative AI, and about the future of society should it be allowed to advance without strict guardrails from the law or from companies.

Data Security and Privacy Concerns

Privacy Risks and Data Breaches: For Generative AI to learn and function properly, it processes and reads large amounts of data it collects from users. In addition to the ethics of collecting private information from users without explicit consent, many are worried about data breaches that can provide bad actors with access to people’s private information, including personal details, financial records, and research data.

Adversarial Attacks and Model Poisoning: In the same vein, attackers who gain access to input data or a program’s code can either inject malicious data or manipulate the code to have the AI system perform functions it was not originally programmed to do. Not only does this compromise the integrity and performance of the AI system, but it can also lead to dangerous outcomes in fields like medicine and automated vehicles.

Malicious Use and Social Engineering: Generative AI’s nature allows it to create highly complex and believable content. Malicious use can take the form of deepfakes, where a person’s face is transplanted onto another person’s body, and the dissemination of misinformation, which has been noted in political campaigns over the past few years. This poses a risk to individuals, organizations, and society as a whole.

Ethical Concerns

Bias and Discrimination: The data that AI learns from is largely programmed by humans, which means that existing biases may be present in the training data. This may lead to biased outcomes that perpetuate existing discrimination in areas like language generation, image synthesis, or hiring.

Intellectual Property and Plagiarism: Generative AI carries the risk of generating content that infringes upon intellectual property rights, since the AI system essentially recreates content it stumbles upon. This may result in cases of plagiarism.

Impact on Human Labor: AI has the potential to take over jobs traditionally performed by human beings, which may result in job losses and further social inequities. However, some argue that as AI automates the market, there will be an increase in creative or human-centered job opportunities.

Contemporary Legal Battles

Exhibit 2023 in the play, which depicts a former employee negotiating the terms of their silence on their former company’s AI practices, draws on the contemporary legal battles shaping AI discourse today.

Suchir Balaji, a former OpenAI engineer and whistleblower who was instrumental in training the artificial intelligence systems behind ChatGPT, was found dead in his San Francisco apartment on November 26, 2024. Although investigators claim it was a suicide, Balaji’s family and friends continue to demand answers to his death, which occurred just before he was set to testify against OpenAI in a copyright infringement case brought by the New York Times.

Baji’s role in the company involved organizing data, online writings, and other media to train GPT-4, the basis for OpenAI’s ChatGPT. Balaji would later question the ethics of the technology he helped build after newspapers, novelists, and others began suing OpenAI and other AI companies for copyright infringement.

Balaji was said to have important and unique “documents” that would have been used in the trial.

The New York Times, in 2025, sued OpenAI for allegedly using the company’s material without its permission to train AI systems. Alongside other publishers like the New York Daily News and the Center for Investigative Reporting, the publishing house feared that chatbots would be able to quickly summarize their work, inadvertently discouraging readers from visiting their websites or seeking the material at the source.

In response, OpenAI claimed its AI models used publicly available data that was protected under “fair use” laws.

“Eighty million dollars says I have to shut up. Doesn’t anybody get it? I’m telling you I made this thing, I helped make this thing, and now…We’re the dinosaurs. We’re the dinosaurs and this is the meteor” (Employee).

Sources for further exploration:

What is Artificial Intelligence (AI)?

IBM

What is Artificial Intelligence (AI)?

Michigan Technological University

AI, Machine Learning, Deep Learning and Generative AI Explained

IBM Technology (Youtube)

Challenges of AI

Washington State University

Ex-OpenAI Engineer Who Raised Legal Concerns About the Technology He Helped Build Has Died

Associated Press

Judge Allows ‘New York Times’ Copyright Case Against OpenAI to Go Forward

NPR

What is the History of Artificial Intelligence (AI)?

Tableau

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

The play begins and ends with exhibit 1816, where, alongside figures Percy Shelley, Lord Byron, Thomas Briggs, and Claire Clairmont, Mary Shelley proposes a story of a scientist named Victor Frankenstein whose fascination with the workings of life leads him to conduct an experiment wherein a creature of severed parts is brought alive with electricity. Eventually, Frankenstein’s creation would murder his close relatives and friends, including his bride, in what could aptly be seen as his “punishment” for defying God.

Frankenstein was, in many ways, a clash between the Enlightenment’s celebration of reason (where humans were viewed as predictable and rationally controllable machines) and the Romantic era’s appreciation of passion and art (where they regarded science with suspicion). Widely regarded as the first true science fiction novel and as one of the first few works to depict the dangers of artificial intelligence, Frankenstein captures the destructive forces of unbridled human creation, especially as it seeks to defy nature and achieve transcendence. The story sends a chilling message: if left to its own devices, an ingenious creation can, and perhaps will, overtake its own creator.

“Only it wasn’t a monster. Victor called the new life a monster because he was scared of it. But its real name was Computer” (Mary).

Sources for further exploration:

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

Stephen Kern (Ohio State University)

Everything You Need to Know to Read ‘Frankenstein’

Iseult Gillespie (TED-Ed)

The Exhibits

In order to preserve the remnants of human civilization, curators have carefully built exhibits that attempt to articulate the story of human history. Each exhibit, in trying to capture the human experience, either illuminates the moments that moved humanity closer to extinction (unbridled human ego) or what the curators call “chasms,” where messy, illogical moments seem to point to an ineffable quality in the lived experiences of people.

Below are some of the exhibits included in the play.

1910: The Second Industrial Revolution

The twentieth century (1900’s) marked the second half of the Second Industrial Revolution, where life in America advanced at a rapid pace. Cities grew, factories sprawled with machinery, automation took further hold of production, and workers’ lives began to revolve around the clock. The price for this progress, however, was the squalor in which workers lived and worked. Many suffered from health consequences (a finger getting cut off) or died as a result of their environments.

Sources for further exploration:

Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire

HISTORY.com

Ford, Cars, and a New Revolution: Crash Course History of Science #28

Crash Course

1987: HIV/AIDS Epidemic

In the 1980’s, the United States became the focal point of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. It was a disease primarily found among men who had sex with other men, which politicized the epidemic during a political context that was increasingly hostile towards the queer community. Leveraging the presence of HIV/AIDS in the gay community, conservatives furthered their condemnation of “immoral” sexual acts, and President Reagan notoriously avoided publicly mentioning the disease until 1985. By 1995, one in nine gay men had been diagnosed with AIDS, and one in fifteen had died.

HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) is a virus that attacks the body’s immune system. Without treatment, it can lead to AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome).

Sources for further exploration:

A Brief History of Civil Rights in the United States: The HIV/AIDS Epidemic

Howard University School of Law

The AIDS Epidemic’s Lasting Impact on Gay Men

Dr. Dana Rosenfeld (The British Academy)

1994: Dial-Up Internet

In July 1992, Sprint became the first company to offer Dial-Up internet commercially, a technology that uses existing telephone lines to connect to the internet. This allowed internet to be accessed from various locations for a relatively cheap price. When Spring first introduced it to the public in 1992, only about 2% of America was online, but by 1995, just three years later, that number crept up to just under 10%.

Starting in the mid 2000’s, cable and telecommunication companies began offering broadband internet connections (cable, DSL, fiber-optics, etc.), which inevitably led to Dial-up Internet’s decline. Today, around 95% of the U.S. population is connected to the internet, the majority of whom rely on broadband internet connections.

Sources for further exploration:

Throwback Thursday: Dial-Up and Our Fondness for the First Internet Connection

Samantha Cossick (Allconnect)

What is Dial-Up

Lenovo

2000: The Flip-Phone

By 2000, Motorola had released two flip phone models: the MicroTAC in 1989 (considered the first flip phone) and the StarTAC in 1996, which kicked off the flip phone’s popularity. The new technology made mobile communication accessible, portable, and in some cases, stylish.

The flip phone would reach peak popularity in the mid-2000’s, but would steadily decline in America by the 2010’s with the advent of the smartphone. Today, flip-phones are making a return with foldable smartphones.

Sources for further exploration:

When Did Flip Phones Come Out? From Iconic Past to Foldable Future

T-Mobile

A Complete History of the Flip Phone

Sixtysix Mag

2008: The iPhone

Just a year before, Steve Jobs introduced the iPhone at the MacWorld Conference in San Francisco on January 9, 2007.

“An iPod. A Phone. And an internet communicator” (Steve Jobs).

Combining a mobile phone, internet access, and iPod music and video playback, the innovative iPhone featured a patented touchscreen technology instead of buttons. It allowed users to watch movies, download songs, store photos, and send emails. It was also the first time the public was introduced to the concept of apps and social media on the go. Today, the iPhone remains the leading smartphone in the United States.

10 Years With the iPhone: How Apple Changed Modern Society

Anthony Karcz (Forbes)

Apple Launches iPhone

Mark Sweney (The Guardian)

2014: Amazon’s Alexa

In 2014, after three years of intense planning and multiple setbacks, Amazon released the Echo. In addition to being a high-end speaker, the 9-inch cylinder device came with an artificially intelligent assistant by the name of Alexa, named after the ancient library of Alexandria.

Confronted by the challenge of developing a system of knowledge for Alexa that would allow it to understand and respond to various types of human speech, Amazon hired a data collection company to secretly record hours upon hours of speech from paid workers around the country.

In choosing Alexa’s voice, the team wanted a certain personality–trustworthiness, empathy, and warmth–and determined that those traits were more commonly associated with a female voice. Atlanta-based-voiceover studio, GM Voices, presented the team with recordings of various candidates, and they ended up picking the voice of actress and singer Nina Rolle.

Amazon Surprises With New Device, a Voice Assistant

Cadie Thomspon (CNBC)

The Secret Origins of Amazon’s Alexa

Brad Stone (Wired)

“So much has been lost, but we have recovered fragments. Scraps of language, abandoned devices. We have endeavored to fill in the gaps; to bring them to life again” (W2).

Science Fiction

Although current AI technologies are capable of advanced tasks–from composing music to providing therapeutic advice to users–the AI of today relies mainly on a process of prediction. This means that AI systems, such as ChatGPT, predict answers to prompts with a high degree of accuracy, thanks to the copious amounts of data on which they’re trained. Thus, no matter how emotionally intelligent or cognizant an AI system may seem, these qualities are, at the end of the day, qualities projected onto them by human users, and not necessarily qualities one can reasonably say they possess. Possession of qualities people ascribe exclusively to conscious beings would require a certain type of AI system that, although purely theoretical, companies have been rigorously working towards–Genera AI.

Artificial General Intelligence, or AGI, is described as an AI system that rivals human capabilities. Aside from being strictly a prediction machine and one that emulates human traits, AGI would feature cognitive and emotional abilities that would arguably be indistinguishable from those of a human. But, because this AI model is purely speculative, there are differing ideas of what an AGI could look like: some argue that it would have full sentience, while others doubt the remote possibility of a machine ever surpassing human intelligence, no matter how advanced. The possibility is daunting for many, and with the rapid pace of modern-day AI technologies, questions about our what will continue to distinguish the human from the machine dominate collective discourse.

However, queries and contemplations about the future of technological advancements are not new. Although the term “science fiction” was only officially coined in the 1920s, past writers have speculated about the cultural, social, and environmental impacts of rapid scientific and technological progress.

How does The Antiquities shed light on our current interactions with artificial intelligence? Is this play, or perhaps science fiction, a useful exploration of the future to come? If so, what impact, if any, does this play, and science fiction as a whole, have on our current actions?

Explore what others have to say about the role of science fiction in society:

What Science Fiction Can Do

Sherryl Vint (MIT Press)

Can Science Fiction Help Us Envision a Better Future?

Ashlee Baker (Yale News)

Can Science Fiction Frame a Better Future?

Dolores Tropiano (Arizona State University)

Science Fiction Inspires the Future of Science

National Geographic

Sources for further exploration:

What You Must Know Before AGI Arrives | Carnegie Mellon University Po-Shen Loh

EO

What is Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)?

McKinsey & Company

Primary trust

Compiled by Reyn Ricafort (Artistic and Engagement Fellow)

On Loneliness

Our Epidemic on Loneliness and Isolation

The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on the Healing Effects of Social Connection and Community

“What is Causing our Epidemic of Loneliness and How Can We Fix It?”

Harvard Graduate School of Education

The Loneliness Epidemic

The Gray Area With Sean Illing (Podcast)

Speaking of Psychology: Why is it So Hard For Adults to Make Friends?

American Psychological Association (Podcast)

An Uphill Battle: Why Are Midlife Men Struggling To Make – and Keep – Friends?

The Guardian

on friendships, community, and kindness

Why Community is So Important – And How to Find Yours

Reader’s Digest

Three Ways to Create Community and Counter Loneliness

Harvard Health Letter

Friendships: Enrich Your Life and Improve Your Health

Mayo Clinic

How to Have Deep Male Friendships with Scott Erickson

Three Percent Co. (Podcast)

Why You Should Talk to Strangers by Kio Stark

TED Talk (Video)

Creating a Community and Finding Your Purpose by Stepehn Jon Thompson

TED Talk (Video)

Acts of kindness and community – building throughout the country

A Look Inside Community Groups Working to Build Trust to Bridge Divides

PBS News

How Penn State’s Employee Resource Group Are Building Community, Belonging

Penn State Human Resources

The Kindness of Strangers: A Nurse Saw Me Crying And Asked If I Wanted a Hug

The Guardian

Leaves Piled Up After Her Husband’s Injury. Then a Friend Showed Up With a Rake

NPR

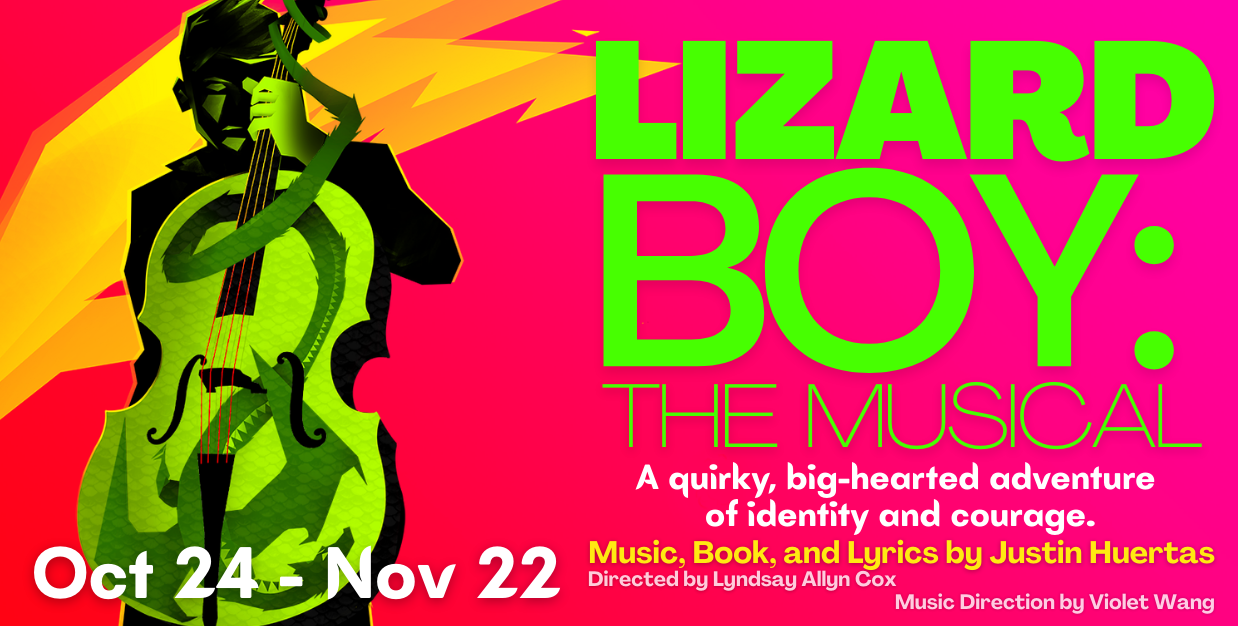

Lizard boy

Written by Reyn Ricafort (Production Dramaturg and Assistant Director)

Mount St. Helen’s Volcano

In Lizard Boy, Mount St. Helens volcano plays a significant role in shaping the trajectory of Trevor’s life. Not only does its initial eruption lead to the protagonists’ scaly green skin, but the possibility of a second explosion drives the play’s action.

The real-life Mount St. Helens volcano is located in Southwestern Washington, 50 miles northeast of Portland, Oregon. Characterized by its steep cone-like structure and explosive eruptions, the volcano is formally classified as a stratovolcano, also known as a composite volcano, due to both its appearance and unique properties.

In 1980, after two months of activity–10,000 earthquakes, hundreds of small explosions, and the outward growth of the volcano’s north flank by more than 20 feet–a 5.1 magnitude earthquake struck beneath the volcano, leading to its eruption on May 19. Playwright Justin Huertas references this historic event in the script, specifying that although the original eruption occurred in 1980, the story’s eruption occurred 20 years ago today.

Temperatures within the explosion reached 570 degrees Fahrenheit, and about 520 million tons of ash were blown across 22,000 square miles of the Western United States. Lahars from the volcano (fast-moving floods of water and volcanic debris) ripped trees from their roots, destroyed 27 bridges, and damaged over 200 homes. The lahars also affected more than 185 miles of highways and roads and killed around fifty-seven people.

After 18 years of relative quiet, the volcano reawakened in September 2004 after a series of intensifying earthquakes. This continued for four more years until 2008.

Further reading:

Mount St. Helens, Washington

USGS

Mount St. Helens Erupts.

HISTORY

Footage of the 1980 Mount St. Helens Eruption

Smithsonian Channel (Video)

1980 MT ST HELENS ERUPTION–FOOTAGE AND PHOTOS

Patrick Croasdaile (Video)

Lizard man

The story’s protagonist, Trevor, is described as having green scales for skin, akin to that of a lizard. In fact, he’s referred to in the play as the “Lizard Boy of Point Defiance.” Although not explicitly based on the classic American folklore, Trevor bears significant resemblance to a similarly reptilian creature native to Bishopville, South Carolina–the Lizard Man of Scape Ore Swamp.

According to the 1988 legend, Lee County teenager Chris Davis was replacing his tires at the edge of Scape Ore Swamp one evening when a lizard-like creature came running at him and attacked his vehicle. Davis held off on reporting the incident to the police out of fear of being mocked until another family from Lee County reported similar strange marks on their car. Davis would even end up taking a polygraph test and passing it upon being questioned about what he saw.

The lizard-like creature was described as standing approximately seven feet tall, with green scaly skin, red eyes, and three toes on each foot. Other reports of damaged cars and chewed-up bumpers would come out in the following weeks, spurring a police investigation that led to the discovery of three-toed footprints around the swamp. The incident attracted news organizations and journalists to Bishopville, garnering the town worldwide attention. Presently, belief in the original myth is ambivalent at best, but the cultural impact of the Lizard Man of Scape Ore Swamp is widely celebrated and remembered.

Further reading:

The Lizard Man of Scape Ore Swamp

City of Bishopville

The Legend of Lizard Man: Horror in Rural Carolina

Swamp Ape Review

Beware the Lizard Man!

Discover South Carolina

American comics and superheroes

Lizard Boy was largely inspired by the comic books playwright Justin Huertas grew up reading and the superheroes he adored: Spider-Man, X-Men, Power Rangers, and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Not only does the play capture the aesthetic qualities of the comic medium (fast transitions, mid-battle quips, split-scenes, etc.), but it also imagines a superhero who more aptly reflects Huertas’s identity as a Queer Filipino-American.

The history of American comics begins in the 19th century, but true American-style comic books emerged later in 1933. The creation of Superman in 1938 kick-started what is known as the “Golden Age” of comic books in America (1938–1956), a period in which the comic book genre gained popularity in the United States with new superheroes like Wonder Woman, Captain Marvel, Batman and Robin, Green Lantern, and Flash.

Part of the genre’s popularity came from its ability to reflect the sentiments and morals of the American population during World War II–comics dramatized stories of good triumphing over evil, loyal superheroes acting on behalf of the greater good, and characters who were courageous and willing to fight for what they believed. Captain America, for example, was created as a symbol of patriotism and some might say, propaganda. Soon after the war, superheroes lost steam, and the Golden Age of comic books came to a halt. This, however, didn’t stop the genre from evolving.

Throughout American history, comic books have consistently reflected the attitudes, cultural shifts, and conversations of the American people. During World War II, in prioritizing American nationalism and patriotism, comic books found themselves employing modes of ethnic stereotyping to articulate the enemy or the “other.” After the war, comics captured the people’s fear of nuclear conflict along with the touted spread of communism.

Naturally, modern-day comics and superheroes grapple with the conversations of today: cultural diversity, climate change, war, gender and sexuality, etc. The expanding discourse on how to champion inclusivity in sectors of life has led to the creation of superheroes and characters that better reflect the diversity of the American people: characters of different religions, ethnicities, genders, and sexualities.

Lizard Boy, in many ways, is Huertas’s attempt to put front and center the facets of his identity he wished he saw in superheroes growing up.

Further reading:

Superhero

Britannica

Comics, Graphic Novels, and Manga

Triton College Library

Superhero Diversity: Improving Diversity in Comic Books

Quality Comix

In Lizard Boy, Justin Huertas is Creating the Queer and Asian Superhero He Wanted Growing Up

Playbill

Social othering

In the play, Trevor’s green skin and reptilian features make him the subject of social rejection and isolation. This can largely be seen as the story’s overarching metaphor for the nuanced experiences of those who’ve been subjected to skin-based prejudice and discrimination. More broadly, however, the metaphor touches upon a societal process known as “othering,” wherein a group of people are fundamentally seen as inferior due to perceived differences, justifying the abuse and mistreatment of individuals.

Although similar, othering differs from categorizing, a natural human instinct to group complex information into classifications to better understand them. However, the content and implications of those classifications are not automatic, but socially constructed. Central to this process is a strong ingroup identity, giving rise to an “us” vs. “them” dynamic wherein the outgroup is stripped of their own identity (characteristics, ideas, backgrounds, and desires) and essentially seen as just members of the “other group.” Often, they are not even seen as human.

Group definitions and boundaries are the result of complex collective and social processes rather than just individual interactions. Through talks, tales, gossip, and stories, the image of a subordinate group is reinforced, leading to behaviors such as racial prejudice, which is then perceived as “natural” and easily attributable to biological difference. Some scholars believe that the physical manifestations of othering start at the normalization of hate speech, meaning that meaningful prevention starts with the words we use.

Effectively countering social othering requires embracing that which is different and promoting an overall atmosphere of inclusivity, rather than stifling difference. Cary exemplifies this by sharing what makes him different with Trevor, albeit minuscule in comparison.

“I hope you learn to understand the monsters in the sky / I hope you ask them questions even as they make you cry” (Trevor, “Eleventh Hour”).

Further reading:

The Problem of Othering: Towards Inclusiveness and Belonging

Othering & Belonging

The Process of Othering

Montreal Holocaust Museum

Queerness

Gay Men of Color

Huertas describes the play as a story about a “queer person of color who learns self-love, self-acceptance, and self-empowerment.” Trevor’s experiences of marginalization as a result of his green skin can be seen through the framework of the exclusion of gay men of color in larger society and in their own community.

Qualitative and quantitative data show that non-white individuals are often placed at the lower end of the sexual hierarchy, while white individuals are placed at the top. In addition to the pressures of obtaining a desirable body (ripped and fit), gay men of color have the added stress of not being “white” enough, resulting in a continual process of subconscious comparison to the ideal, leading to a general feeling of anxiety.

On dating apps like Grindr (which is more accurately a hook-up app), gay men of color are either outright excluded in the name of sexual preference or racially fetishized. Although the latter functions on inclusion, it hinges on racially specific sexual characteristics that are inherently racist. The experiences of racial minorities result in racialized feelings, or the set of feelings that specifically have to do with one’s race, which dramatically affects the way they see and perceive the world. The material consequences of racialized feelings can manifest in the body or in one’s behaviors.

This explains, in part, Trevor’s outburst near the end of the play where he assumes the worst from Cary–he carries with him the visceral expectation of rejection, an expectation that has colored his perception of other people.

The majority of Grindr users are white, and research has shown that race is an important predictor of online connections and offline meetups. An interview study found that online, Black and Asian men were disproportionately rejected by white men and racial minorities compared to white men.

“He knows I’m green and still said come over so maybe I’m not…just a boy who looks like a lizard.” (Trevor, “Willy Nilly”)

Further reading:

For Queer Men of Color, Pressure to Have a Perfect Body is About Race Too

Them

Feeling Like a Fetish: Racialized Feelings, Fetishization, and the Contours of Sexual Racism on Dating Apps

The Journal of Sex Research

People of Colour Say Racism, Exclusion, Fetishization, Rampant in LGBTQ+ communities

CBC

Loneliness Among Gay Men

In the play, loneliness affects both Trevor and Cary, albeit in different ways: Trevor feels lonely because of his green skin and previous romantic fallout, whereas Cary’s loneliness stems from his lack of friends despite regularly engaging in hookups.

Loneliness is generally understood as a subjective experience; one can be surrounded by lots of people and still feel lonely. Much of the loneliness gay men feel begins in adolescence, when they first taste the exclusionary experience of being different from other boys. Patterns of emotional withdrawal (keeping to oneself) are then carried over to adulthood.

Research shows that gay men and queer individuals experience higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression, all of which contribute to feelings of loneliness. Researchers largely attribute these negative emotions to minority stress–the extra effort it requires to be part of a minority group. Gay men experience loneliness not because of an inherent defect, but because of structural heteronormativity and homophobia. Gay men may be primed to expect rejection, and thus go about life carrying this fear of exclusion, whether they realize it or not. For gay men of color and for those who don’t fit the ideal beauty standards, exclusion in their own community is not uncommon.

Researchers generally agree that the antidote to loneliness is community, and although exclusion towards members runs rampant in gay spaces, it seems like the solution is to keep looking (be brave like Trevor), steer clear of unhealthy behaviors, and be selective about where one looks and who one forms bonds with.

Further reading:

Why Do Gay Men Often Deal With Feelings of Loneliness?

The Roots of Loneliness Project

The Epidemic of Gay Loneliness

Huffington Post

Experiences of Loneliness Among Gay Men: A Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis

Journal of Homosexuality

Grindr

Throughout history, sexual minorities have sought to create their own networks where they can meet outside the purview of a generally unwelcome society. In the play, Trevor and Cary meet on one such network–Grindr.

Started in 2009, Grindr is a geo-location social “networking” app for the LGBTQIA+ community. More colloquially, however, it is known as a “hookup” app. Profiles are spread out on a grid, organized by location, where users can view other users and directly message them if they are interested. Unlike dating apps like Tinder or Hinge, users need not have mutual interest to message one another and send photos. In addition to sex, people use Grindr for dates, friends, actual “networking”, or simply to kill time.

Grindr receives its fair share of criticism for promoting a hook-up culture that many say only exacerbates systems of exclusion in the gay community, which in turn leads to feelings of loneliness. This critique is not exclusive to Grindr, however, as social media as a whole seems to be undergoing a period of critical interrogation by the general public. In truth, conventional research paints a more complicated picture and often produces mixed results.

For example, one study found that intimate self-disclosure (disclosing personal details about oneself to another user) on Grindr decreased feelings of loneliness because it provided queer people a safe space to discuss their sexuality. There seems to be a difference between direct communication (private messages to people online) and passive media consumption (scrolling through Instagram). This same study found that passive consumption increased feelings of loneliness.

If we can assume that the majority of Cary’s hookups were from Grindr, then his persistent feelings of loneliness despite those engagements support that networks like Grindr have only exacerbated social isolation. At the same time, Grindr plays an important role in connecting Trevor and Cary, kickstarting what would become a profoundly meaningful relationship for both characters. Truthfully, the consequences of Grindr are a little bit more nuanced in the story, just like in real life. If the story makes anything certain, it’s that genuine relationships are not only beneficial but necessary to understanding our worth as individuals.

Further reading:

Social Consequences of Grindr Use: Extending the Internet-Enhanced Self-Disclosure Hypothesis

Cornell University

What is Grindr?

Grindr

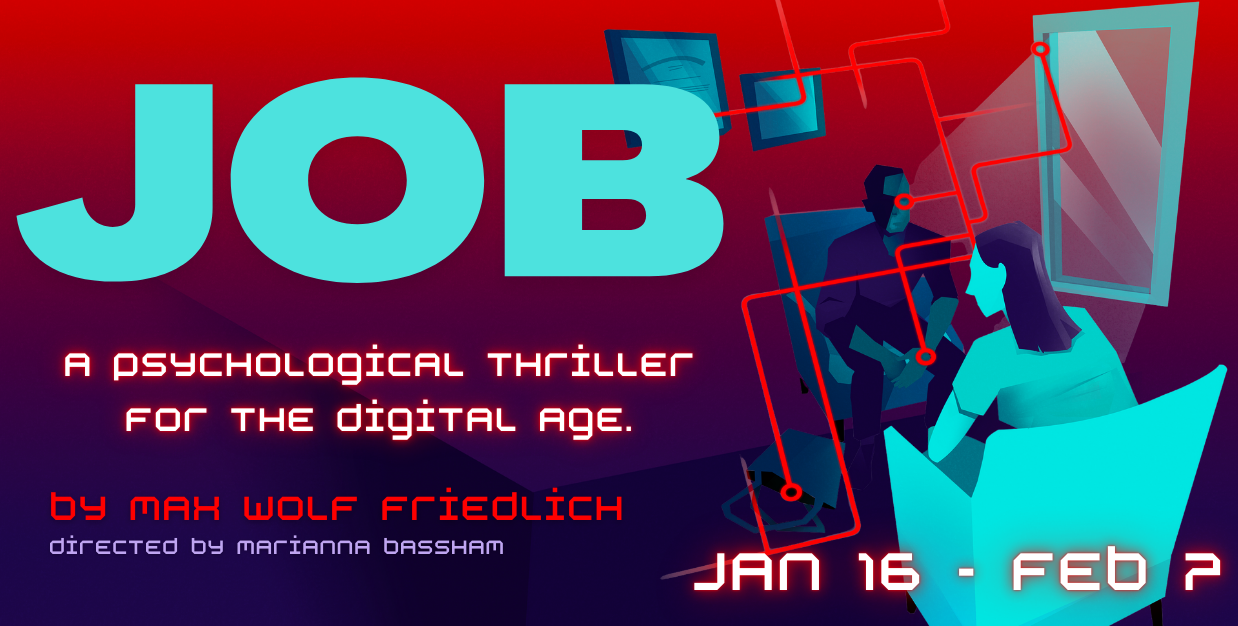

JOB

Written by Reyn Ricafort (Artistic and Engagement Fellow) and Margaret Rankin (Assistant Director)

Mental health and the internet

Doomscrolling

As a content moderator at a tech company, Jane is exposed to violent imagery on a regular basis. Although most internet users are not tasked with finding and getting rid of abusive content, many find it difficult not to come upon disturbing news while simply perusing online spaces. While some can simply log off if they wish, others are unable to look away and find themselves gravitating toward negative information – this is known as doomscrolling, the tendency to consume news that elicits anxiety, sadness, or anger.

Some research suggests that the brain has a bias towards negative information. Indeed, our ancestors relied on that spark of brain activity to detect and avoid dangerous situations. According to neuroscience, encountering negative news triggers stress signals that prompt the user to continue scanning for threats, much like early humans. At the same time, doomscrolling releases feel-good chemicals (dopamine) every time new information is seen, a key neurochemical in addictive behaviors. This creates a negative feedback loop wherein the user experiences momentary anxiety before feeling rewarded–doomscrolling.

Repeated exposure to negative news puts one’s body in a constant state of panic, or fight-or-flight, leading to emotional and physical fatigue, also called burnout. Symptoms include a lack of motivation, hopelessness, depression, apathy, and withdrawal, among others.

With the events of the current world essentially compressed inside smartphones, it’s easy to fall into the trap of doomscrolling, a predicament many online users find themselves in. Although Jane’s obsessive doomscrolling is incentivized by a job and a personal obligation she feels towards the world, the effects of this behavior on the brain are in clear view in the play, even if she herself doesn’t see that:

“…as soon as I’m fully awake, I start to panic–it’s a panic I’m so used to at this point that it’s almost comforting” (Jane).

Further exploration:

Doomscrolling Again? Expert Explains Why We’re Wired for Worry

Sara Bock, UC San Diego

Constant Coverage of Scary News Events Can Overwhelm the Body

Mayo Clinic

Max Fisher on How Silicon Valley has Rewired our Brains

Offline with Jon Favreau (YouTube)

How False News Can Spread – Noah Tavlin

TED-Ed (YouTube)

Growing up on the Internet

Jane and Loyd come from different generations and understandably have differing perspectives on politics, culture, and the use of technology. Loyd, born before the digital age, is considered a digital immigrant, someone who likely required a bit more time to adapt to technology, while Jane, a digital native, can be assumed to have more dexterity with it. With research supporting that technology significantly affects the developing brain, it’s worth speculating how much of Jane’s disposition in the play is in part influenced by her interactions with technology growing up.

The adolescent brain has been found to be more sensitive to social feedback, which explains the rise of anxiety, embarrassment, mood swings, and need for social acceptance during adolescence. Exposing the still-developing adolescent brain to social media makes users more susceptible to developing addictive behaviors later on, like doom scrolling or “brain-rot,” a popular term used to describe the perceived cognitive decline of those who consume copious amounts of media.

Indeed, research seems to support that excessive screen time is associated with negative outcomes: lowered self-esteem, increased incidence and severity of mental health issues, poor concentration, and cognitive decline. Passive consumption itself, not necessarily of negative news, reduces capacity for sustained attention and focus, which fosters feelings of detachment, loneliness, and disconnection. Since Jane seems to exhibit most, if not all, of these emotions, is it fair then to establish a link between Jane’s mental state and her early exposure to technology? Or does that reading risk minimizing the circumstances that push her to the edge?

“Perhaps we’ve traded psychedelics for a slow drip of dopamine that comes from these devices in our pockets” (Loyd).

Further exploration:

Demystifying the New Dilemma of Brain Rot in the Digital Era: A Review

Yousef, Ahmed Mohamed Fahmy et al.

The Impact of Social Media Scrolling on Brain Development

Gary Goldfield, Psychology Today

Fatigue, Traditionalism, and Engagement: the News Habits and Attitudes of the Gen Z and Millennial Generations.

American Press Institute

What is Information Technology? Each Generation’s Thoughts.

Novadean Watson-Williams, American Military University

Being a Citizen of the Internet

Moderating online spaces, for Jane, means grappling with the often abusive content people willingly post. Understandably, Jane is driven to her wits’ end, along with other things going on in her life, leading to her mental breakdown in the office. But even this moment of vulnerability isn’t safe from the whims of internet users, as Jane finds herself dodging the public attention she’s acquired from her breakdown video going viral.

Thus, the play asks, what does it mean to be a citizen of the internet? With roughly 75% of the U.S. public using more than one social media platform, this question is essential. Moreover, a study shows that over 23% of adults say they’ve shared fabricated stories online.

Is there a “right” way to use the internet? What would that look like? What is our responsibility to other internet users? But, internet ethics goes both ways–what responsibility does the internet have towards the people who use it? Should it take a moral stance? Or would that prevent its supposed neutrality that allows for the free-flow of information without bias?

“I’m famous and nobody knows who I am” (Jane).

Read the sources below to see what experts have to say:

What is Digital Citizenship?

Canada’s Centre for Digital Media Literacy

Are You A Good Digital Citizen?

Social Integrity, University of Michigan

What is Internet Ethics?

Santa Clara Markkula Center for Applied Ethics

Social Obligation

“…but if they actually wanted to do something – like the degree they claimed – they’d kill their parents and redistribute the inheritance” (Jane).

A large part of what motivates Jane to continue doing the work she does, no matter how difficult, is the sense of responsibility she has toward fighting injustice in the world. She believes this pursuit requires extracting what’s “bad” in the world and storing it in one’s body, effectively implying that social justice asks for some degree of self-sacrifice. However, the self-sacrifice that Jane exhibits in the play seems to call for a complete breakdown of the self; after all, it’s merely in proportion to the gargantuan level of injustice that exists in society.

Unsurprisingly, Loyd challenges Jane’s despairing view, although, dramaturgically, it’s difficult to take his word on the nuances of morality.

What kind of responsibility do we have in addressing injustices? Is there a proper way to approach it? Is self-sacrifice inevitable? Or is there a way to maintain our well-being while fighting for equity in contemporary society?

Visit the sources below to see what other people have to say:

Injustice is Everywhere, so What are our Moral Duties?

Kieran Setiya (BBC)

What Kind of Responsibility Do We Have For Fighting Injustice? A Moral-Theoretic Perspective on the Social Connections Model

Academic Article on Marion Young’s Social Connections Model

I’m Angry About the Injustices Around Me

Mental Health America

The Antidote to Climate Anxiety

The Gray Area with Sean Illing

Content Moderation

Jane’s company calls her position “User Care,” whereas other companies may classify it as “Content Moderation.” Regardless of the name, the responsibilities are the same: moderating online spaces for content that violates company policies. This often refers to content that is deemed inappropriate, abusive, illegal, or factually untrue. With the growing rise of users on social media platforms (over 5 billion as of 2025), the amount of misinformation and harmful content has understandably risen in proportion. Thus, over the past few years, companies have had to seriously grapple with how they choose to moderate their online spaces, and the political and ethical implications of their choices.

Before social media became a ubiquitous presence, the responsibilities of content moderation largely fell on human moderators and community efforts. But by the 2010’s, the volume of content being generated across platforms required artificial intelligence models (AI) to oversee a large bulk of supervision. Today, the majority of content moderation is performed by AI algorithms, but many companies still rely on a hybrid model that involves human engagement. While AI is good at detecting explicitly harmful content, human moderators are needed for those that may require a bit more contextual judgment (i.e., content concerning someone’s age).

Similar to how Jane describes her job in the play, real-life content moderators experience similarly harrowing conditions that lead to understandable breakdowns in their mental well-being. One moderator describes being forced to supervise 5-6 hours/week of child sexual abuse material despite being promised only 1-2 hours/week.

Despite the risks of allocating content moderation to a select few employees as opposed to a whole team, media companies over the past few years have downsized their content moderation departments largely due to costs. In 2023, both Google and Amazon downsized teams and departments responsible for combating harmful information. Just this past year, Meta (formerly Facebook) announced that it would end its third-party fact-checking program on all domains. The current downsizing of content moderation also falls squarely under a presidential administration that many have described as pandering to right-wing criticism that social media platforms suppress conservative viewpoints. Whether this has credibly incentivized companies to downsize their content moderation efforts is unclear, but the link is compelling.

All this begs a larger question: If cutting back on moderation leads to more misinformation online, who is this benefiting and how?

“But the bots can’t do everything–there are errors, toss-ups, mistakes that require someone to physically review the thing.

And that’s what I do, that’s who I am.” (Jane)

Further exploration:

Google and YouTube Moderators Speak Out

The Verge (Video)

The Role of Content Moderators: What they do and why are they needed?

Zevo Health (Video)

What Is a Content Moderator? We Interviewed a Pro

Basedo

YouTube Loosens Rules Guiding the Moderation of Videos

New York Times

Tech layoffs ravage the teams that fight online misinformation and hate speech

CNBC

Tech layoffs shrink “trust and safety” teams

NBC

WOMEN IN TECH

Although women’s representation has grown, STEM fields have largely been dominated by men. From the cultish culture of tech industries to the presence of sexism, racism, and classism in these spaces, below are some works to plunge deeper into the unique experiences of women working in tech.

Uncanny Valley: A Memoir (2020)

Anna Wiener

After leaving a job in the New York publishing world, Anna Wiener lands a position at a big-data startup in the country’s technology epicenter: Silicon Valley. The memoir chronicles her navigation of a world brimming with unchecked ambition, ride-or-die corporate attitudes, and the recklessness of companies vying for the top spot.

Hidden Figures (2016)

20th Century Studios

Hidden Figures brings to light the overlooked stories of Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan, and Mary Jackson, three Black female mathematicians at NASA who were instrumental in the historic launch of John Glen into orbit in 1962.

The Dropout (2022)

Searchlight Television

A biographical drama series that follows Stanford dropout Elizabeth Holmes and her rapid rise to fame with her now-defunct blood-testing company, Theranos, and the ruin that ensues after her company’s fraudulent and misleading practices are brought to light.

We’re All Going to the World’s Fair (2021)

Jane Schoenbrun

A teenage girl, Casey, takes the “World’s Fair Challenge”, an online role-playing horror game, and documents the mental and physical changes that happen to her.

*This movie does not necessarily explore women in tech, but was one of the works cited by playwright Max Wolf Friedlich in the author’s notes, in addition to “Uncanny Valley.”

Past Productions

Past Productions The Antiquities

The Antiquities Swept Away

Swept Away